Explosives trail

A tour around the site of the Pitsea Explosives Factory

A walk through history

Around 100 years ago there was an explosives factory on the site of Wat Tyler Country Park.

The Pitsea Explosives Factory produced nitroglycerine, guncotton and all sorts of explosives for mining and for war.

Follow the signs around the Wat Tyler explosives trail and uncover the evidence of a huge and complex operation that spread right across the whole park site.

The Wat Tyler explosives trail

Follow route on Google Maps (opens a new window).

- Factory entrance

- Site stores

- Laboratory

- Expense magazine

- Water collection and lab magazine

- Cartridge huts

- Liquids recycling and acid egg house

- The magazines

- Nitrating house & flushing tanks

- Nitroglycerin mixing house

- Gelatine mixing houses

- Dangerous energy

- Cordite range

- Site offices

- Guncotton washing

- Wet process storage

- Cordite room & non-hazardous store

- Packing house

- Tramway to wharf

- Washing bowl

- A bump in the landscape

1. Factory entrance

The building here was originally the Pitsea explosives factory search hut.

Workers were searched for metal objects that could cause a spark – matches, coins, watches, jewellery. It was feared a spark could ignite volatile fumes and blow up the factory, as had happened in a number of factories around Europe.

The buildings opposite were the guard house and supervisor’s house.

Staff were kept on site to guard against accidents or sabotage by enemy agents during wartime. Explosives were a very profitable business, and the company had to keep its guard up against foul play by ruthless competitors.

2. Site stores

The land where the Green Centre now stands would most likely have been the location for the explosives factory’s general stores.

Non-explosive items like sheets of brass for manufacturing cartridges, or glass vials for storing and dispensing acids would have been kept here along with uniforms, machinery and spare parts.

3. Laboratory

This building became the explosives factory’s laboratory after the original laboratory (standing on the site of the house next door) was destroyed in an accident in 1916.

Laboratory staff tested the strength of incoming chemicals to guarantee uniformity and safety, as consistent blends and strengths were vital for making reliable explosives that were safe to handle and use.

Chemicals that fell below standard could lead to fatal accidents. In 1913 an explosion thought to be caused by sub-standard guncotton led to three deaths, extensive damage and a report to Parliament.

Finished explosives were also tested here by igniting a small amount of the explosive on a bench top.

4. Expense magazine

Electricity and gas were not used in the explosives factory site in dangerous areas, as they might ignite the highly flammable fumes created in explosives manufacture. This meant work in the factory was limited to the hours of daylight.

If at the end of the day’s work a batch of explosives wasn’t finished, the unfinished batch would be stored here in the expense magazine until light returned, allowing the workers to finish the work the following morning.

Fumes in the factory buildings could be so overpowering that workers would frequently pass out. Fellow workers would then pull their unconscious workmate out of the building and leave them in the fresh air until they recovered. As soon as they came round, they went straight back to work.

5. Water collection and laboratory magazine

The natural-looking ponds here were actually man made. They were designed to capture waste water from washing guncotton, an explosive made by mixing cotton waste from the Lancashire mills with nitroglycerin – the most frighetningly unstable and powerful explosive.

Guncotton was washed in water to remove excess nitroglycerin and to make it stable enough to be handled safely and easily. To get rid of any lingering traces of nitroglycerin in these ponds, once a week a worker was given the job of throwing a charge of dynamite into the pond.

The building to the side of the pond was the laboratory magazine. It stored chemicals used for testing explosives ingredients and explosives in the laboratory.

6. Cartridge huts

A series of small wooden ‘cartridge huts’ followed the perimeter track here, where workers assembled ammunition for guns.

Women workers took pre-cut explosive ‘charges’ and used machinery to press them into brass cylinders (cartridges) that held the explosive and allowed it to be easily loaded into a gun.

The ‘charge’ would explode inside the cartridge case, forcing a lead bullet out at great speed through the barrel of a rifle or pistol.

7. Liquids recycling & acid egg house

The angular earthworks you see all around the park are called blast mounds. They were built around and between the buildings of the factory to contain accidental explosions and stop them spreading from building to building.

The recycling house stood within the blast mound here. It was used to recover as much of the precious acids used in the chemical processes as possible, as these represented a high proportion of the cost of manufacture. The challenges of acid production and distribution meant many larger factories would have their own acid manufacturing and distillation facilities on site.

Further along this path are the remains of the acid egg house, where compressed air was used to gently and safely remove sulphuric and nitric acid from the large cast iron ‘eggs’ they were delivered in.

8. The magazines

Around this perimeter track there were five magazines, each holding about 1.5 tons of nitroglycerin-based explosives.

Magazines had brick walls and wooden roofs. In case of an explosion the blast would meet least resistance going upwards and out through the roof. Blast mounds around each magazine would also help direct the blast upwards instead of sideways, preventing damage to neighbouring factory buildings.

Wooden floors were secured with copper nails to avoid causing sparks and possibly igniting the explosives.

9. Nitrating house & flushing tanks

Producing nitroglycerin – the most volatile and dangerous of all explosives – was actually a very boring job. It happened here in the nitrating house, where nitric acid was carefully mixed with glycerin in a large vat with a factory worker keeping a constant eye on the temperature of the mix.

This job was so boring that workers were made to sit on a one legged stool to avoid falling asleep.

If the mixture in the vat got too hot then the worker would have to quickly flush the system with water to douse the chemical reaction, then release the mixture for recycling and start again with a new mixture.

The nitroglycerin produced here at the highest point of the factory site was piped by gravity to other buildings at lower positions around the site.

10. Nitroglycerin mixing house

Workers in the mixing houses mixed nitroglycerin with an inert paste to stabilise the explosive and make it easier to handle. Alfred Nobel pioneered this technique and called the explosive it produced dynamite.

Different mixtures were used to give different strengths and blasting qualities, depending on the intended use. Explosives for ammunition were blended to propel missiles at speed, whereas explosives for quarrying were blended to fracture even the hardest rock.

Others were mixed to explode with very little flame to minimise the risk of igniting flammable gases in mines.

11. Gelatine mixing houses

The buildings that stood here at one time made gelignite, a newer type of nitroglycerine explosive that followed on from dynamite. It contained a higher concentration of nitroglycerin and was used extensively for blasting rock in mining and laying railways.

Its experimental development cost the lives of many workers in Europe who died in accidental explosions.

By 1913 four of the buildings were being used as “stoves” to dry gun cotton. In that year the northernmost stove exploded, tragically killing two people.

12. Dangerous energy

Whatever chemical process went on in the huts that would have stood inside these blast mounds we can’t know for sure – but the earthworks here give us a clue.

These are two of the largest blast mounds on the site and are surrounded by double bonded blast mounds, suggesting that a very dangerous chemical process must have gone on here.

Concrete channels in the bases of these huts suggest they were used for handling acids, and were probably built to manufacture a new type of explosive using new techniques.

13. Cordite range

The buildings that stood here housed large machinery including presses that forced newly-mixed dynamite through circular dies to make tubes of dynamite in different diameters. These were then cut to length to make dynamite ‘sticks’ for mining, or ‘charges’ that went into military shells and ammunition for rifles and pistols.

Dynamite sticks would then be wrapped in greaseproof paper and packed into crates at the packing house, ready for use in mining. Charges went to the cartridge huts where they were pressed into cartridges for military use.

14. Company offices

This building would have housed the site offices, where the customers’ orders for different explosive blends would have been received and relayed to the foremen and workers on the ground

15. Guncotton washing house

The Wat Tyler Centre building could have been where guncotton was ‘washed’ in nitroglycerin in huge open tanks to stabilise the explosive.

The floors of all buildings on the site which dealt directly with explosives were covered in sheets of lead to avoid causing sparks and igniting the explosives.

While the guncotton was wet it was safe to handle. The next stage, where the guncotton was heated and dried on the drying stoves, was one of the most dangerous processes on the site, and one that led to fatal accidents.

16. Wet process storage

5 corrugated iron sheds stood here. They were probably used to store the materials needed in the nitroglycerin washing house ‘wet’ process.

Factory buildings were carefully separated between hazardous and non-hazardous processes, and staff were made to wear either red or green uniforms, depending on the kind of process their job involved.

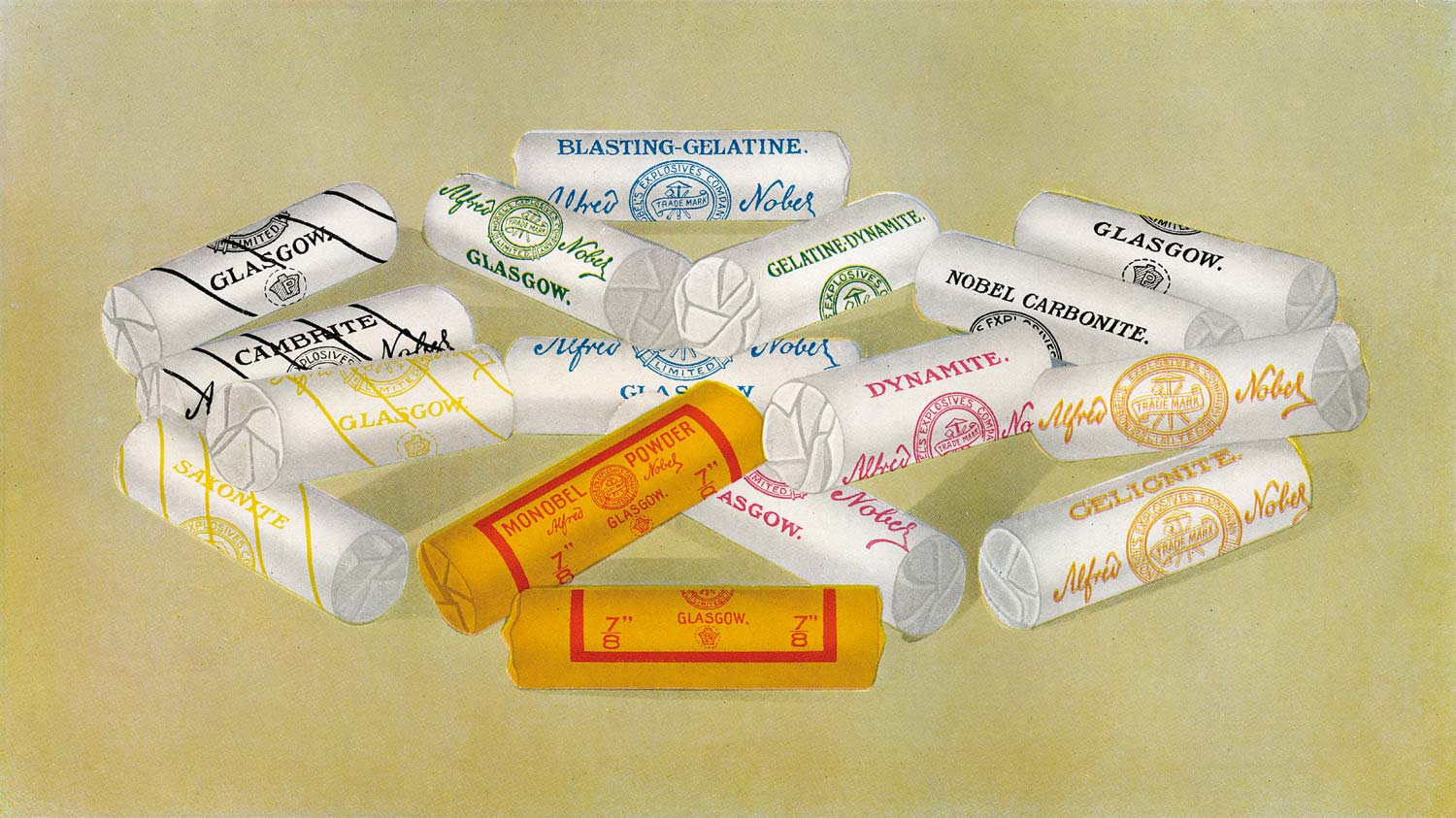

Every explosive manufactured on this site was based on nitroglycerin. Different product names like Dynamite, Cordite and Blasting Gelatine were given to explosives with different characteristics developed using different manufacturing techniques, materials, and strengths.

17. Cordite room and non-hazardous store

The entrance to the play area stands on the site of a building where Cordite was once made. Cordite was the British Government’s answer to the Swedish Alfred Nobel’s inventions of nitroglycerin and dynamite.

Nobel tried to take the government to court for patent breach, but the different wording on the British patent made it impossible for Nobel to sue, even though the chemical process was nearly identical.

18. Packing house

The packing house was supplied by the tramline (which the miniature railway now retraces in part), making it easier and safer for explosives to be off-loaded into the building.

The building itself was used for packing explosives into boxes so they could be transported safely and securely to the client.

Explosives were loaded onto barges from the wharfs and shipped to a special explosives mooring at Hole Haven (where the creek meets the Thames) and then onto larger ships.

19. Tramway

The current miniature railway stands in the place of part of the old tramline which supplied many of the buildings on site.

Trams of several carriages were drawn by a horse walking to one side of the track. Wooden rails were used some distance before each building to prevent sparks.

The tramline still leads to the third of three wharfs (the other two were on the landfill site). This wharf, positioned close to a number of buildings, would have been used as a goods inwards wharf, for off-loading safe incoming materials.

Finished explosives were dispatched from an isolated wharf that can still be seen next to the landfill site down the creek. If a cargo exploded there it would be well away from the rest of the factory, limiting potential damage and disruption to production.

20. Washing bowl

The unusual concrete bowl that sits beyind the fence towards the creek was probably used to wash or drain guncotton.

You can see where itwould have been lined with bronze, chosen to prevent sparks and reactions with any of the chemicals being used.

On the far side of the concrete bowl you can see a channel for draining its contents.

21. A bump in the landscape

This magnificent view from this spot looking out over the marshes towards the Thames shows the big drop in height from the middle of the park to its perimeter – one of the main reasons this site was chosen for an explosives factory.

The drop in height made the process of moving chemicals around from one building to another easier, safer and cheaper. A sprawling network of pipelines criss-crossed the factory site supplying acids and water to all the chemical processes involved in explosives manufacture.

More than 90 interconnected buildings peppered the site in the factory’s heyday.